What Was The First Japanese Full Length Animated Film In Color?

In this inquiry note I intend to hash out some aspects of the history of the earliest Japanese blitheness films for the cinema. The offset task is to assemble from the literature a list of all such films shown in 1917. I will then introduce a hitherto unknown contemporary source on SHIMOKAWA Ōten's 下川凹天Imokawa Mukuzō Genkanban no maki 芋川椋三玄関番の巻 (Imokawa Mukuzō – The Janitor) which has been widely, just apparently wrongly, considered to have been the start Japanese blitheness film, and look into the chronological society of Shimokawa's films in the get-go half of 1917. In the third part I try to plant the animation techniques used in 1917, before looking more than closely at two other gimmicky Japanese sources with an American background. Based on an analysis of these texts I contend that at to the lowest degree two of the three pioneers of Japanese animation somewhat overstated their own ingenuity and the obstacles they had to overcome in developing these techniques respectively.

I. The animation films of 1917

There is, at to the lowest degree, no uncertainty about the identity of these three pioneers:

• SHIMOKAWA Ōten 下川凹天 (also read Shimokawa Hekoten, born Shimokawa Sadanori 下川貞矩, 1892-1973), a manga artist, worked for the motion-picture show company Tenkatsu 天活 (Tennenshoku Katsudō Shashin KK 天然色活動写真株式会社), probably from around the middle of 1916 to belatedly in 1917.(ane)

• KITAYAMA Seitarō 北山清太郎 (1888-1945), who had been trained in Western painting, seems to have adult an involvement in animation in the second half of 1916 and approached another big flick company, Nikkatsu 日活 (Nippon Katsudō Shashin KK 日本活動写真株式会社), in January 1917 (Tsugata[2007], p. 277) He left Nikkatsu again at some stage to establish his own animation studio in the fall of 1921 (Tsugata[2007], p. 143).

• KŌUCHI Jun'ichi 幸内純一 (also read Kōuchi Sumikazu, 1886-1970), another manga creative person and friend of Shimokawa'southward,(2) was asked in Feb 1917 past KOBAYASHI Kisaburō 小林喜三郎 (1880-1961), who had split from Tenkatsu and founded the film company Kobayashi Shōkai 小林商会, to produce animation films. This lasted until about the end of 1917 when the visitor's financial troubles became crippling. In 1923 Kōuchi founded own animation studio "Sumikazu" スミカズ (Adachi[2012], pp. 61f., 67).

In that location is also wide agreement among Japanese animation experts on the number, titles and cinema premières of animation films in 1917, all of which were made past these three people:(iii)

• Imokawa Mukuzō Genkanban no maki 芋川椋三 玄関番の巻 (Imokawa Mukuzō – The Janitor; hereafter Genkanban): Shimokawa, January 1917 [but see below];

• Dekobō shingachō – Meian no shippai(4) 凸坊新画帳・名案の失敗 (Dekobō'south new picture book – Failure of a great program; hereafter Meian): Shimokawa, first ten days of February 1917;

• Chamebō shingachō – Nomi fūfu shikaeshi no maki 茶目坊新画帳・蚤夫婦仕返しの巻 (Chamebō's new picture volume – The revenge of Mr. and Mrs. Flea; hereafter Nomi): Shimokawa, 28 April 1917;

• Imokawa Mukuzō Chūgaeri no maki 芋川椋三 宙返りの巻 (Imokawa Mukuzō – Somersault; time to come Chūgaeri): Shimokawa, middle ten days of May 1917 – Mukuzō flies happily in the air but then falls downwardly; quite skillful for a Japanese product simply the lines are sometimes growing thick and sometimes sparse, which stands out markedly; there's quite a lot of room for further research (The Kinema Record, vol. V, no. 48, 15 June 1917, p. 302);

• Saru to kani no gassen サルとカニの合戦, as well Saru kani gassen猿蟹合戦 (The war between monkey and crab): Kitayama, 20 May 1917;

• Yume no jidōsha 夢の自動車(5) (The dream machine): Kitayama, final ten days of May 1917 – Dekobō dreams that his bed turns into a auto und drives around; there's much research still to exist done; the senga 線画 (6) should, of course, finely portray the motion; in the future it would be important that the plot be given attention, as well (The Kinema Tape, vol. V, no. 48, 15 June 1917, p. 302);

• Namakuragatana なまくら刀 (The blunt sword)(7), also Hanawa Hekonai Meitō no maki 塙凹内名刀の巻 (Hanawa Hekonai – The famous sword), also Tameshigiri 試し斬 (The sword test): Kōuchi, xxx June 1917;

Postcard by the National Film Center, Tokyo, showing frames from Namakuragatana.

(From Matsumoto Natsuki'due south collection.)

• Neko to nezumi 猫と鼠 (True cat and Mice)(eight): Kitayama, 4 July 1917;

• Itazura posuto いたずらポスト (Naughty mailbox): Kitayama, 28 July 1917;

• Chamebō Kūkijū no maki 茶目坊空気銃の巻 (Chamebō ‒ Air gun), also Chame no kūkijū 茶目の空気銃 (Chame's air gun): Kōuchi, 11 August 1917;

• Hanasaka-jiji 花咲爺 (The old human who made flowers blossom): Kitayama, 26 August 1917;

• Imokawa Mukuzō Tsuri no maki 芋川椋三釣の巻 (Imokawa Mukuzō goes fishing; future Tsuri), also called Chamebōzu Uozuri no maki 茶目坊主魚釣の巻 (Chamebōzu goes fishing): Shimokawa, 9 September 1917 – Mukuzō goes fishing but fastens the fishing line to a motorcar which ends in failure; clownish (The Kinema Record, vol. 5, no. 50, October 1917, p. 26; mid- September is given in that location for the opening appointment);

• Chokin no susume 貯金の勧 (What to practice with your postal savings): Kitayama, 7 Oct 1917(ix);

• (Otogibanashi –) Bunbuku chagama (お伽噺・)文福茶釜 ((Fairy-tale:) Bunbuku kettle): Kitayama, ten October 1917;

• Shitakire suzume舌切雀 (Sparrow with no tongue): Kitayama, eighteen Oct 1917;

• Kachikachiyama カチカチ山 (Kachikachi Mountain): Kitayama, 20 October 1917;

• Chiri mo tsumoreba yama to naru 塵も積もれば山となる (Great oaks from little acorns grow)(10): Kitayama, completed at the finish of 1917 (Tsugata[2007], p. 118);

• Hanawa Hekonai Kappa matsuri 塙凹内かっぱまつり (Hanawa Hekonai – The Kappa festival): Kōuchi, old in 1917(11).

SHIBATA Katsu(12) 柴田勝 (1897-1991), who was a cameraman for Tenkatsu at the time, mentions two farther films by Shimokawa which apparently are non listed anywhere else: Bunten no maki 文展の巻 (The Ministry of Culture'due south art exhibition (13)) and Onabe to kuroneko no maki お鍋と黒猫の巻 (The pot and the black cat) (Shibata[1973], 8).(fourteen)

II. Concerning Imokawa Mukuzō Genkanban no maki and other films by Shimokawa

There is widespread agreement in the literature that Shimokawa's Genkanban was the start Japanese animation film to be shown in a picture palace, in this example in January 1917 in the Asakusa Kinema Kurabu 浅草キネマ倶楽部, a theater in Tokyo managed directly by Tenkatsu(15). Only sometimes practice nosotros find an explicit annotation of doubt, such as with AKITA Takahiro who mentions that there is no tape of Genkanban'due south showing and that Meian might have been the first instead, simply leaves the question open up because of a lack of sources (Akita[2005], p. 94).

In fact, scarcely any study gives a source for the claim that Genkanban was, a) the showtime Japanese animation film, and b) that information technology premiered in January 1917. The earliest source for a) that I know of is Shimokawa's article in 1934: he writes that Genkanban was his commencement film, and the first Japanese animation, and shown in the Asakusa Kinema Kurabu (Shimokawa[1934]); but he does not give a date.(xvi) Information on b) must have come from some other source, possibly from an commodity on Japanese blitheness in the July 1917 issue of the film journal The Kinema Record (Kinema rekōdo キネマ・レコード) which states that the first animation, by Tenkatsu, was shown in January 1917 (Wasei kāton[1917]), (17) but provides no title.

In the May 1917 issue of the same journal, however, we detect the following, up to at present overlooked or ignored, notice in a column chosen Motion picture Visits: April:

"Kinema Kurabu: Imokawa Mukuzō Genkanban no maki – Mr. Imokawa's Janitor (Tenkatsu). It is Tenkatsu's tertiary senga trick. I'chiliad glad about such an attempt. The title is fetching. Information technology is skilled." (Firumu kenbutsu[1917], p. 240) (18)

In other words, this source – which seems to be non just the merely contemporaneous 1, but also the earliest past far contradicts the standard business relationship of the offset of Japanese blitheness film. It suggests that Genkanban was not the starting time film past Shimokawa and Tenkatsu, and thus the first Japanese blitheness moving picture, nor was it shown in Jan, but in April 1917.

Which leads us to the question: How credible is this source? There is no prima facie reason to doubt The Kinema Record. Information technology had earlier identified Meian as the "second senga trick", opening at the Kinema Kurabu quondam during the outset x days of February 1917, and it had given a brief description: "Mukuzō tries to capture a boar, digs a pit, and brings about a big failure" (The Kinema Tape, vol. 5, no. 45, x March 1917, p. 140).The dates it gives for Chūgaeri and for Tsuri besides hold reasonably with those listed past Yamaguchi and Watanabe, which seem to come up from some other source (Yamaguchi/Watanabe[1977], p. 192).

As well, it is unlikely that the reviewer saw a rerun of a picture already shown in January, merely did not recognize it as such, especially because his comment near "such an attempt" and "skilled". That the motion picture had already been completed in Jan, just was released only in April, is not likely either.

Now the question arises: How apparent is Shimokawa'due south article from 1934? One signal worth noting in this context is that Shimokawa claims that just one monthly film magazine existed when he began his piece of work in animation (Shimokawa[1934]). But in 1916 there were, at the least, two such magazines – Katsudō no sekai 活動之世界 and The Kinema Record, in 1917 Katsudō gahō 活動画報 was added. And so he did make mistakes.

Moreover, the structure of his commodity is a bit strange. First he goes into his being hired by Tenkatsu, so he discusses his blitheness techniques (blackboard and paper blitheness, see below), the second of which he holds responsible for his eye impairment and the subsequent end of his career in animation. He mentions Kitayama and Kōuchi. Only so, seemingly deviating from his chronological narrative, does he assert: "The first piece of work Imokawa Mukuzō Genkanban no maki and ii others opened at the Kinema Kurabu" (Shimokawa[1934]).

How tin can nosotros reconcile these contradictory sources? Considering that all of his films that we know of for certain opened at the Kinema Kurabu, it would seem possible that Shimokawa here refers not to his very first blitheness picture, done in an inferior technique, but to the beginning one done with the new technique, which he wanted to have remembered and which might well have been Genkanban (but run into below). In that case, the "two other" films would, pre presumably, have been Chūgaeri and Tsuri.

Simply this leaves usa with a troublesome question: What to practise with Nomi, which is said to have premiered on 28 April 1917? I take not been able to identify the source for the opening appointment or the production information on Nomi, but see no reason to doubt the existence of such a record. If information technology was shown afterward Genkanban, as would seem probable considering its première tardily in April, it would presumably have been fabricated with the new technique, too, but then Shimokawa should take written about iii, rather than ii other films. Moreover, this would squeeze three films, including Chūgaeri, into at most 1 and a half months, whereas the concluding(?) film came four months afterward.

Or was Nomi in fact only an culling title of Genkanban? This would explain a lot,(xix) but information technology would seem to collide with testimony by Shibata if we assume Genkanban and the subsequently Chūgaeri were made with the new technique. According to a text past him quite closely based on his production diary, Shimokawa's, and Tenkatsu'south, first blitheness motion picture – chosen past Shibata Hekobō shingachō 凹坊新画帳 (20) – was only made in mid-April 1917, and used the old technique (Shibata[1974], p. 51). This might so refer to Nomi or, though unlikely, to an otherwise unknown moving picture. In the 1973 version of his memoirs, which was written later than the i (re)published in 1974, Shibata explicitly notes Chūgaeri every bit the film he worked on with Shimokawa, just uses a pseudonym for himself and does not mention the championship given in his 1974 version (Shibata[1973], p. 8; Ōshiro[1995], p. 66). All the same at that stage he plainly had done some research (he quotes from The Kinema Tape's review) implying that he had attempted to place which title he had actually filmed. As The Kinema Record does non list Nomi, he may have been led astray and mistaken information technology for Chūgaeri ‒ a motion picture that would take come to the cinema quite late for being filmed in mid-April anyway.(21) If Hekobō shingachō was Nomi, then Genkanban must accept been produced and shown in the movie house very shortly afterwards, which is possible but also ways that three films (Nomi, Genkanban, and Chūgaeri) were produced inside virtually a month using two different techniques.

Another solution would be to assume that Genkanban and Nomi were just ii titles of the same film, opening in late Apr 1917, but produced with the onetime technique and filmed by Shibata. Why the reviewer of The Kinema Tape would then applaud Genkanban, nevertheless, would remain a bit of a mystery.

We could get around this by making a different assumption: that Shibata erred in the date of his filming the ominous Hekobō shingachō. In fact, in the 1974 version – which I consider the more reliable of his two publications, fifty-fifty if it was all the same non the original product diary – he does non give an accented engagement. Rather he mentions this work every bit having been filmed between coming dorsum from on-location filming on Mt. Myōgi in Gunma Prefecture for the 29th picture he fabricated with a manager (7 to ix April 1917), and the long-awaited commencement film of his ain, for which he travelled to Kamakura on 15 April. But he does non put a number to Hekobō shingachō; after his second own pic comes the 30th film with a director (Shibata[1974], p. 51).

Might he actually have filmed Dekobō shingachō – Meian no shippai, in January or early February? However, we should notation that Shibata's placing this picture betwixt a long excursion to the mountains and the first picture show he made alone sounds like a true memory; it might also be hard to clasp Hekobō shingachō into his before schedule. On the other mitt again, assuming that Hekobō shingachō was Meian would be helpful for the considerations below on blitheness technique and would mean that Shimokawa had had enough fourth dimension to alter his technique for Genkanban.

It might also muddle the question of what actually was the beginning blitheness moving-picture show by Shimokawa. Both the entry on Meian ("2nd senga fox") and subsequently the article on Japanese cartoons in The Kinema Record point to an blitheness pic produced by Tenkatsu and shown in January 1917, yet none seems to take been recorded at the fourth dimension.(22)

In the version of his memoirs written later on, Shibata claims that a "manga dekobō shingachō" マンガ凸坊新画帳 (apparently meant equally a generic championship, non an individual ane) was completed by Shimokawa already in 1916 (Shibata[1973], p. 6). Only in the 1974 version he obviously did not know near that and asserted that Hekobō shingachō had been the first animation.

Thus an animation film past Shimokawa only may, not must, take been shown in January 1917, not necessarily at the Kinema Kurabu. The Yūrakuza 有楽座cinema in Marunouchi 丸の内, Tokyo, for instance, held a Tenkatsu animation festival ("dekobō taikai" 凸坊大会) with imported films commencement on ten January 1917 (Asahi shinbun, 10 January 1917, p. 7). (23) Maybe a Shimokawa picture show was besides presented in that location. In the end, however, we do not know anything (all the same) about such a moving picture. For the fourth dimension being, therefore, Dekobō shingachō – Meian no shippai has to exist regarded as the oldest confirmed Japanese animation movie. Genkanban came subsequently. Withal we must likewise have that information technology is non possible to be fully confident about how many films Shimokawa really made and in which order, without finding mistake with at least i of the sources.

III. Animation techniques

With just one film extant from 1917 (Kōuchi's Namakuragatana), and another one from February 1918 (Kitayama'south Urashima Tarō (24) 浦島太郎), both discovered by Matsumoto Natsuki in 2007 (Matsumoto[2011], p. 97), we have to rely on the literature to an unusual degree to find out about the techniques used by Japan'southward animation pioneers.

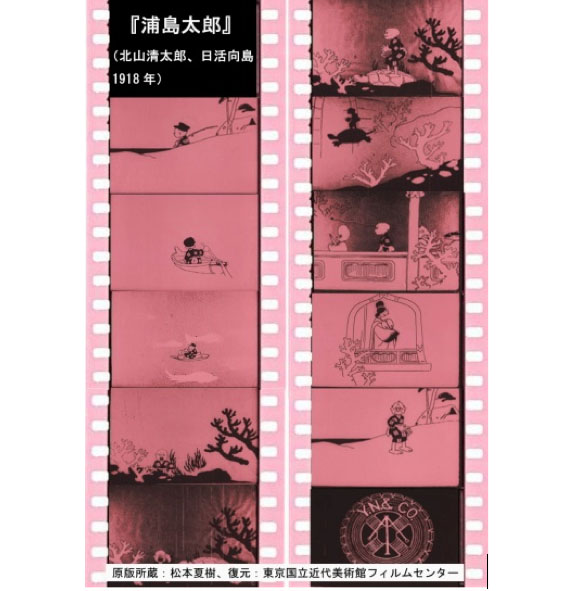

Postcard by the National Film Heart, Tokyo, showing frames from Urashima Tarō.

(From Matsumoto Natsuki's drove.)

Concerning Shimokawa's films, we have his own article from 1934 in which he states that he at first used chalk on blackboard, with those portions changing from picture to pic being wiped away and drawn anew. This method, however, was uncomfortable and couldn't be perfected, and so he changed to paper animation, using three types of printed backgrounds on which he drew the characters freehand, whitening out any lines on the groundwork that would interfere. For this technique he likewise constructed a kind of worktable, consisting of ii boxes on which lay a glass plate illuminated from below by a strong lite (Shimokawa[1934]).

Shimokawa gives no clear indication when exactly this change in technique occurred. However, since he mentions that he used his work tabular array for about one-half a year before constantly looking into the strong calorie-free caused him centre damage, and because his concluding pic seems to accept opened in September, it can be deduced that he would have begun using paper animation roughly between Feb and June 1917. (25) This would besides represent with Shibata's statement that Shimokawa still used the blackboard technique in mid-April (Shibata[1974], p. 51) or, if we use the assumption introduced above, for Meian in late January, early February.

Whereas we can therefore be quite certain that Shimokawa start employed blackboard animation and then paper animation with printed backgrounds, the date of the changeover cannot be established precisely, with March 1917 beingness the almost probable, in my stance.

Kitayama too used ii techniques in 1917/18. At beginning, according to an article on Nikkatsu in the Oct 1918 issue of Katsudō no sekai (quoted in Tsugata[2007], p. 95), he used a method called "kōgashiki" 稿画式, then, "lately", "kirinukigashiki" 切抜画式. While the latter is patently cut-out blitheness, the old is explained by TSUGATA Nobuyuki as "today'south paper blitheness, the method where, starting with the background to the people etc. and moving stuff, everything is fatigued on one sheet" (Tsugata[2007], p. 95).

Yet, the memoirs of Kitayama'southward assistant YAMAMOTO Sanae 山本早苗 (a.k.a. Yamamoto Zenjirō 山本善次郎, 1898-1981) give a different impression. He mentions that the sheets with the moving characters, fabricated from a special paper, were laid upon background sheets before existence filmed (Yamamoto[1982], p. 82). (26) In fact, because Kitayama'due south output and his use of (a few) assistants, it would have made sense to separate the cartoon of backgrounds, which could be re-used, from the drawing of the moving characters. But Yamamoto also confirms that Kitayama so proceeded to cutting-out animation (Yamamoto[1982], p. 83).

Over again, nosotros cannot pinpoint the moment when the changeover occurred. However, Urashima Tarō already employed cut-out animation plus drawn animation, and so it would accept been before February 1918, and likely already in 1917.

The situation regarding Kōuchi's animation technique is somewhat easier because, while we don't seem to have a statement from him, his start film Namakuragatana clearly employs cut-out animation, with some fatigued animation thrown in. In that location is no reason to presume that he changed this with his later films in 1917; in fact, he still used cutting-out animation at the end of his career (Manga firumu[1930]).

Iv. Knowledge about foreign animation techniques in 1916/17

In retrospect both Shimokawa and Kitayama claim that they had no written reference fabric to learn from. Shimokawa wrote in 1934: "[…] then I could not simply think nearly everything myself" (Shimokawa[1934]). In his volume on animation published in 1930, Kitayama stated that he had "solved the machinery [of Western animation] in my caput" (quoted in Tsugata[2007], p. 66). He also claimed: "Research at the desk began. There were no reference books or such. There was non fifty-fifty a fragment of a senga film" (quoted in Tsugata[2007], p. 70).

In this context Tsugata mentions a Japanese article based on an American one and published in the February result of Katsudō gahō, simply does non chronicle its contents (Tsugata[2007], p. 72). In a afterward publication he additionally refers to an article from 1916, but claims that these were but outlines and that 1 could not acquire all about animation from them (Tsugata[2010], p. 14).(27)

Yet the relevant signal here is not whether one could acquire everything from these articles, only whether they would have provided the basic inspiration for animation techniques. If we look first at the article The Story of Dekobō Shingachō by the pseudonymous Shōfūsei (28), published in Katsudō no sekai in November 1916, we run across that it starts with early animation in France, but then shifts to the US, with a special accent on John Randolph BRAY (1879-1978).(29) At that place follows a part on animation techniques and filming: "Now, formally the filming method of 'Dekobō gachō' is exceedingly unproblematic. There are mainly two methods …". The first is cut-out animation on fatigued backgrounds, which is said to be called "blithe cartoon" in foreign countries.

The second method is based on flip-books ("katsudō ehon" 活動絵本), simply more than precisely fatigued and extended to reach the length of a film (Shōfūsei[1916], pp. 28f.). Again, the backgrounds are separately drawn in batches of tens or fifty-fifty hundreds, and simply the moving bodies are then fatigued in with the slight variations necessary for giving the appearance of movement. But this method is laborious both for the ane who draws the pictures and for the ane who operates the camera, because the drawings have to be centered exactly. So, if the cut-outs from the first method are moved on the backgrounds during filming, this might be the all-time and "allow birds fly freely through the heaven and permit Chame move fully like a living human beingness, coming out from the left, entering to the correct, going in all directions" (Shōfūsei[1916], pp. 29f.).

At that place follows information about filming, near the number of frames necessary for a film, about economizing (Bray is said to film one drawing three to five times in a row and all the same to get a excellent consequence), and about perspective and depth in the backgrounds. At the end we find a list of by and large American companies and their artists whose work had recently been shown in Japan: Rubin, American Pathé, Universal, Powers… (Shōfūsei[1916], pp. 30f.). All in all, this commodity does not read similar a translation of an American one, but seems to have been written from a Japanese viewpoint, based on American materials.

In February 1917 Katsudō gahō published an article that was clearly marked as a translation from an American original. The periodical Scientific American had published an essay on Animated Cartoons in the Making in its upshot of 14 October 1916, and a slightly rearranged and abbreviated version of this was published in Japanese by the again pseudonymous Rakuyōsei (30) . Two pieces of information from this business relationship of cel blitheness should be noted hither: "The various backgrounds of the moving manga [katsudō manga 活動漫画] are only drawn once each.' (Rakuyōsei[1917], p. 33)

As well, a worktable is described for use by the animator. In this case one piece of information was, in fact, lost in the translation: "The master artist works on an easel consisting of a slanted piece of ground drinking glass held in a suitable frame, through which pass the rays of an electric lamp placed beneath it" (Blithe Cartoons[1916]; accent added). The Japanese translation, on the other manus, just says "glass" (Rakuyōsei[1917], p. 34).

Shimokawa might take needed normal drinking glass anyway, as he could not use cels, merely only newspaper, all the same this missing particular is revealing and may have contributed to his going bullheaded on his correct center (cf. Ōshiro[1995], p. 66).

Of course, this article, as well, includes more information, but these data should suffice for the question at hand. If nosotros consider the animation techniques of Shimokawa, Kitayama and Kōuchi, we find that simply Shimokawa's blackboard animation is not covered here. Obviously, Shimokawa had watched – or heard about – some of the oldest foreign animated films for the movie house, perhaps even James Stuart BLACKTON's (1875-1941) Humorous Phases of Funny Faces from 1906, which was bachelor in Japan, although nosotros do not know when information technology was shown in theaters, if at all (Litten[2013], p. 4). That film was done as blackboard blitheness, and several of Emile COHL's (1857-1938) films, including parts of Les Exploits de Feu Follet alias Nipparu no henkei ニッパルの変形, which premiered in Japan in 1912 (Litten[2013]), looked every bit if they were made in the same way.

Merely it would exist hard to fence that Shimokawa's change in technique was not due to the commodity in Katsudō gahō. Likewise, that change would take come subsequently the article had been published in Feb 1917, perhaps even immediately afterwards, if Shibata erred in placing his work on a Shimokawa film in mid-Apr.

Equally far as Kitayama and Kōuchi are concerned, both were very probable influenced past either or both of these articles (witness Kitayama's worktable equally described past Yamamoto). It would be difficult to believe that they did not discover those articles when they were trying to detect out how to do animation. And fifty-fifty if they did non, someone at the companies who paid them surely would accept alerted them to this content. Obviously, putting it into practice was still difficult work, merely the claims Shimokawa and Kitayama subsequently made about their discovering the secrets of blitheness on their own would seem to be highly dubious. (Kōuchi does not seem to accept made similar claims.)

Conclusion

The primeval history of Japanese blitheness film is still partly clouded. While we know the identity of its three pioneers – Shimokawa Ōten, Kitayama Seitarō, and Kōuchi Jun'ichi, several problems remain. The offset Japanese blitheness flick that we can exist sure of was Shimokawa's Dekobō shingachō – Meian no shippai for Tenkatsu, which opened in early February 1917. Information technology was very likely fabricated using blackboard blitheness. Imokawa Mukuzō Genkanban no maki followed in April, probably made every bit paper animation with printed backgrounds. If in that location was a film past Shimokawa opening already in January 1917, nosotros have no information on it, not even a championship. The new list of the very earliest Japanese animation films, all fabricated past Shimokawa, would thus read:

• [unknown title in January 1917, existence uncertain;]

• Dekobō shingachō ‒ Meian no shippai: start ten days of February 1917;

• Imokawa Mukuzō Genkanban no maki: Apr 1917; might be identical with, or later than

• Chamebō shingachō – Nomi fūfu shikaeshi no maki: 28 April 1917;

• Imokawa Mukuzō Chūgaeri no maki: center ten days of May 1917

For Kitayama'south and Kōuchi'southward films the state of affairs is better: Kitayama's Saru to kani no gassen came out on 20 May 1917 using newspaper blitheness, probable with dissever backgrounds; Kōuchi's Namakuragatana followed on xxx June 1917 using the cutting-out animation which would soon go the standard technique for Japanese animators. With the exception of Shimokawa's primeval movie(s?), which seems to have been inspired by older Western animation, all of these films were very likely blithe using American techniques and ideas, every bit collected and translated in two articles published in Japanese film journals in tardily 1916 and early 1917. The roots of Japanese animation do take a stiff American flavour.(31)

FOOTNOTES

I would like to give thanks Astrid Brochlos, INOUE Momoko 井上百子, MATSUMOTO Natsuki 松本夏樹, and Andreas Wendlberger for their help in accessing some of the sources used for this note in a timely fashion. This note was offset published on i June 2013; this is a slightly improved, final version.

(1) This assumption is based on Shimokawa'due south own recollection from 1934 (Shimokawa[1934]). Nonetheless, as volition be shown, this source is not necessarily reliable, and the dates are in any case vague.

(2) He wrote 1 of the two prefaces to Shimokawa's first book Ponchi shōzō ポンチ肖像 (Dial Portraits) in 1916 (Ōshiro[1997], p. 130).

(three) The post-obit list is based on the standard history by Yamaguchi/Watanabe[1977], p. 192f. Farther information on content is only included as a paraphrase in cases where neither this book nor Tsugata[2007], p. 118, contains whatever (and I happened upon it). None of the films seems to have exceeded a length of xv minutes, nigh were much shorter.

(iv) The championship is given as information technology appears in The Kinema Tape, vol. V, no. 45, x March 1917, p. 140. The later literature unremarkably calls it Dekoboko shingachō – Meian no shippai 凸凹新画帳・名案の失敗, which would translate as Bumpy new picture book – Failure of a bully program. "Dekobō" 凸坊and "Chame" 茶目and variants afterwards refer to manga characters by KITAZAWA Rakuten 北沢楽天 (1876-1955). "Dekobō shingachō" was a generic championship for animation films at the time (meet Litten[2013], v).

(5) 自働車 in the original is presumably a misprint; come across also Yamaguchi/Watanabe[1977], p. 192. Tsugata[2007], p. 118 and elsewhere, writes Yume no jitensha 夢の自転車 (The dream bike), just has no information on the content.

(6) "Senga", literally "line motion picture", is used here for animation.

(7)Afterwards stating "with regret" that animation was a foreign invention, an commodity based on an interview with ŌFUJI Noburo (1900-1961), a disciple of Kōuchi, mentions in 1933 Namakuragatana ナマクラ刀by TERAUCHI[!] Jun'ichi 寺内純一 as ane of the outset Japanese blitheness films, besides the otherwise unknown, and probably wrongly remembered, Dekobō shin mangachō 凸坊新漫画帳 by Kitayama Seitarō (Mina-san ga daisukina "Manga no Katsudō"[1933]).

(8)Translations of Kitayama titles from here on based on Tsugata[2003], p. 21.

(9)This advertising motion-picture show was already described as ane of iii films presented past the Ministry of Communications on xi August 1917 to encourage the use of postal saving accounts. Another film in this package to bout Japan was a foreign produced version of The emmet and the grasshopper, possibly too an animation film (Katsudō shashin[1917]).

(ten) Literally, If grit accumulates, it volition grow into a mountain.

(11) For unknown reasons, the most recent endeavour to listing all anime omits this film, as well equally Meian, Yume no jidōsha, and Chiri mo tsumoreba yama to naru (Stingray/Nichigai[2010], p. 891).

(12) He is read Shibata Masaru by Tsugata (east.g., Tsugata[2007], p. 109), only the National Diet Library catalogue, not e'er reliable either, reads his name as Shibata Katsu.

(13) This translation assumes that "bunten" 文展 is an acronym for "Monbushō bijutsu tenrankai" 文部省美術展覧会. The topic would seem somewhat unusual for Shimokawa.

(14) Shibata[1974] mentions only i film past Shimokawa by title, run into beneath.

(fifteen) In improver to the literature already mentioned, e.k.: Okada[1988], p. 111; Animēju henshū-bu[1989], p. 4; Yamaguchi Yasuo[2004], p. 46; Tsugata[2010], p. 13; Matsumoto[2011], p. 96.

(16) There has also been, for instance, a claim for another championship, Kitayama'due south Saru to kani no gassen, to have been the first Japanese blitheness film. (Forty years history of Nikkatsu, published in 1952, p. 81, quoted by Ōshiro[1995], p. 65).

(17)Even so, according to Tsugata[2007], p. 98, this source had up to then been rarely introduced.

(eighteen)「キネマ倶樂部 / 芋川椋三玄關番の巻 Mr. Imokawa's Janitor (天活) / 天活第三次の線畫トリックだ。こういふ、試みは嬉しい。タイトルが馬鹿に氣に入った。巧妙である。」

(nineteen) It would also, for instance, make Imokawa Mukuzō the "star" of all films certainly made by Shimokawa. On Imokawa's "background" every bit a manga character, see Ōshiro[1995], p. 66ff.

(twenty) Either a misprint for Dekobō shingachō, or a pun on Shimokawa'southward proper noun, simply presented as if it were an private, not a generic, title.

(21) According to Shibata'southward records films seem to take usually premiered less than a calendar week after the cease of his work. See for example the dates of his 29th and 30th film for a director (Shibata[1974], p. 51). His quoting from the review does not necessarily mean that he remembered the film'southward content, too, later more than one-half a century.

(22) However, in that location seem to have been quite a lot of picture palace-related periodicals in early 1917 which probably have not been examined notwithstanding. Cf. Kisha no koe[1917].

(23) At an before "dekobō taikai" at the Yūrakuza, in July 1916, Kitayama seems to accept kickoff encountered blitheness (Tsugata[2007], p. 64f.). Yamamoto[1982], p. 77, more than specifically points to a film by the Fleischer Brothers.

(24) The Japanese version of Rip van Winkle.

(25) The long gap between Chūgaeri and Tsuri might accept been caused by this change, but it might also be explained by Shimokawa'due south "foreign affliction" which he contracted in addition to his eye trouble (Shimokawa[1934]).

(26) Yamamoto here too mentions a worktable (tōshaki 投射机) with a light below. At the time one could non become electricity while the sun was still high, unless one had a mill. And so they had to wait until the afternoon to start using it (Yamamoto[1982], p. 82).

(27) Both sources are also mentioned in Hagihara[2008], 266.

(28) This is but a guess at the reading of the name.

(29) Bray's Colonel Heeza-Liar series was well received in Japan, as an article in The Kinema Record shows, also (Wasei kāton[1917]).

(xxx) Cf. annotation 28.

(31) Whether the very early imports of German blitheness and their likely imitation, the film strip Katsudō shashin 活動写真, were seen past the pioneers of Japanese movie theatre animation is unknown. See Litten[2014].

SOURCES

Adachi Gen 足立元: Kusari wo hikichigirō to suru otoko – "Kindai shisō" no sashi-e ni tsuite 鎖を引きちぎろうとする男 –「近代思想」の挿絵について. In: Shoki shakaishugi kenkyū 初期社会主義研究, no. fifteen, 2012, pp. 55-79.

Akita Takahiro 秋田孝宏: "Koma" kara "firumu" he. Manga to manga-eiga「コマ」から「フィルム」へ。マンガとマンガ映画. Tokyo: NTT, 2005.

Animated Cartoons in the Making. In: Scientific American, vol. 115, 1916, no. xvi, p. 354.

Animēju henshūbu アニメージュ編集部 (ed.): Gekijō anime 70 nenshi 劇場アニメ70年史. Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten, 1989.

Asahi shinbun 朝日新聞, 10 January 1917, p. 7.

Firumu kenbutsu ‒ shigatsu no maki フィルム見物 四月の巻. In: The Kinema Record キネマ・レコード, vol. V, no. 47, 15 May 1917, p. 239-240.

Hagihara Yukari [萩原由加里]: 1930 nendai kara 40 nendai no Nihon anime seisaku ‒ tebikisho wo chūshin ni [1930年代から40年代の日本アニメ製作 手引書を中心に]. In: Core Ideals, vol. four, 2008, pp. 266-275.

Katsudō shashin de kanyi hoken no kan'yū 活動写真で簡易保険の勧誘. In: Asahi shinbun 朝日新聞, 12 August 1917, p. 5.

The Kinema Tape キネマ・レコード, vol. 5, no. 45, 10 March 1917, p. 140.

The Kinema Record キネマ・レコード, vol. 5, no. 48, fifteen June 1917, p. 302.

The Kinema Record キネマ・レコード, vol. V, no. 50, October 1917, p. 26.

Kisha no koe 記者の声. In: The Kinema Record キネマ・レコード, vol. V, no. 44, x February 1917, p. 96.

Litten, Frederick S.: On the earliest (foreign) animation films shown in Japanese cinemas. 2013. http://litten.de/fulltext/nipper.pdf (accessed on ten May 2013).

Litten, Frederick Southward.: Japanese color animation from ca. 1907 to 1945. 2014. http://litten.de/fulltext/colour.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2014).

Manga firumu no seisakuhō wo kaiso Kōuchi Jun'ichi-shi ga hanashite kureru 漫画フィルムの製作法を開祖幸内純一氏が話してくれる. In: Yomiuri shinbun 読売新聞, xx Oct 1930, p. v.

Matsumoto Natsuki 松本夏樹: Eiga torai zengo no kateiyō eizō kiki – gentō, animēshon, gangu eiga 映画渡来前後の家庭用映像機器 – 幻燈・アニメーション・玩具映画. In: Iwamoto Kenji 岩本憲児 (ed.): Nihon eiga no tanjō 日本映画の誕生. Tokyo: Shinwasha, 2011, pp. 95-128.

Mina-san ga daisukina "Manga no Katsudō" dōshite tsukurareru ka? [皆さんが大好きな「漫画の活動」どうして作られるか?]. Asahi shinbun朝日新聞, 19 March 1933, p. 5.

Okada Emiko おかだえみこ: Nippon no anime 70-nen no kiseki 日本のアニメ70年の奇跡. In: Okada Emiko おかだえみこ et.al. : Anime no sekai アニメの世界. Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1988, pp. 111-125.

Ōshiro Yoshitake 大城冝武: Shimokawa Hekoten kenkyū (two) – Nihon no okeru animēshon eiga no reimei 下川凹天研究 (2) – 日本におけるアニメーション映画の黎明. In: Okinawa Kirisuto-kyō tanki daigaku kiyō 沖縄キリスト教短期大学紀要, no. 24, 1995, pp. 63-74.

Ōshiro Yoshitake 大城冝武: Shimokawa Hekoten kenkyū (iii) – Hekoten nenpū kōchū 下川凹天研究 (3) – 凹天年譜校註. In: Okinawa Kirisuto-kyō tanki daigaku kiyō 沖縄キリスト教短期大学紀要, no. 26, 1997, pp. 125-139.

Rakuyōsei? 落葉生: Dekobō shingachō no seisakuhō ‒ saientekku[!] amerikan shosai 凸坊新画帳の製作法 – サイエンテックアメリカン所載. In: Katsudō gahō 活動画報, vol. 1, 1917, no. 2, pp. 32-36.

Shibata Katsu 柴田勝: Tenkatsu, Kokkatsu no kiroku 天活、国活の記録. Tokyo: Shibata Katsu, 1973.

Shibata Katsu 柴田勝: Katsudō shashin wo omo to shita watashi no jijoden 活動写真を主とした私の自叙伝. In: Eizō-shi kenkyū 映像史研究, 1974, no. iii, pp. 45-59.

Shimokawa Ōten 下川凹天: Nihon saisho no manga eiga seisaku no omoide 日本最初の漫画映画製作の思ひ出. In: Eiga hyōron 映画評論 (Eiga hyōron sha), 1934, no. 7, p. 39.

Shōfūsei? 松風生: Dekobō shingachō no hanashi 凸坊新画帳の話. In: Katsudō no sekai 活動之世界, vol. ane, 1916, no. 11, pp. 28-31.

Stingray スティングレイ, Nichigai Associates 日外アソシエーツ (eds.): Anime sakuhin jiten アニメ作品事典. Tokyo: Nichigai Assembly, 2010.

Tsugata Nobuyuki: Research on the achievements of Japan'due south start three animators. In: Asian Movie theatre, Spring/Summertime 2003, pp. 13-27.

Tsugata Nobuyuki 津堅信之: Nihon-hatsu no animēshon sakka Kitayama Seitarō 日本初のアニメーション作家北山清太郎. Kyoto: Rinsen Shoten, 2007.

Tsugata Nobuyuki 津堅信之: Japan no shoki animēshon no shosō to hattatsu 日本の初期アニメーションの諸相と発達. In: Anime ha ekkyō suru アニメは越境する. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2010, pp. nine-thirty.

Wasei kāton, komedi wo miru 和製カートン、コメディを見る. In: The Kinema Tape キネマ・レコード, vol. V, no. 49, 15 July 1917, p. 339.

Yamaguchi Katsunori 山口且訓, Watanabe Yasushi 渡辺泰: Japan animēshon eigashi 日本アニメーション映画史. Osaka: Yūbunsha, 1977.

Yamaguchi Yasuo 山口康男: Nihon no anime zenshi. Sekai wo sei shita Nihon anime no kiseki 日本のアニメ全史。世界を制した日本アニメの奇跡. Tokyo: Ten-Books, 2004.

Yamamoto Sanae 山本早苗: Manga eiga to tomo ni 漫画映画と共に. Tokyo: privately published, 1982.

Source: https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/the-first-japanese-animation-films-in-1917/

Posted by: smithbelve1956.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Was The First Japanese Full Length Animated Film In Color?"

Post a Comment